Why Athletes Load Manage: Protecting the Body for the Long Game

If you have ever watched a top athlete withdraw from a match or sit out a game and thought, really, again, you are not alone. Fans, pundits, and even some coaches have voiced frustration when a player deemed fit enough to compete chooses not to. But behind those decisions, more often than not, is something far more considered than laziness or caution gone too far. There is a body that has been worked hard, a pain that has been building quietly, and a very deliberate plan to make sure that body can keep going.

Load management has become one of the more talked-about concepts in modern sport, and not always in a flattering way. But the athletes and sports physiotherapists who rely on load management know something that the wider conversation tends to miss: chronic pain in sport is real, it is cumulative, and if you ignore it long enough, it will make the decision for you.

This piece is about understanding why load management exists, why athletes choose it, and why the science behind it is more compelling than the critics would have you believe.

The Reality of Chronic Pain in Sport

Chronic pain in athletes does not usually arrive with a bang. There is no dramatic moment, no single incident you can point to and say, that is where it started. It creeps in. A tightness after training that takes a bit longer to ease each week. A dull ache in the knee that used to disappear by Thursday but now lingers into the weekend. A shoulder that clicks in a way it never used to.

For athletes who have trained since childhood, many of these sensations become background noise. You learn to filter them out, to push past discomfort because that is what the sport demands. The problem is that the body does not forget. Years of repetitive movement, high-impact landings, and relentless training volume leave a mark on tendons, bones, joints, and muscles. Not all of it is visible, and not all of it is immediately felt.

The conditions that tend to define chronic pain in sport are telling in their nature. Tendinopathy, where a tendon becomes overloaded and degenerates over time, is extraordinarily common in running, jumping, and throwing athletes. Persistent lower back pain haunts rowers, weightlifters, and cyclists. Stress fractures that do not heal fully before the next season begins become recurring problems. Freak injuries they are not; overuse injuries like these are the result of tissue that has been asked to do too much, too often, without adequate recovery.

Then there is the psychological side, which gets talked about far less than it should. Living with chronic pain changes how an athlete relates to their sport. Fear of re-injury shapes every movement decision, often subconciously. Confidence erodes. The joy that used to come from competing gets replaced, at least in part, by a kind of anxious management. Calling this weakness misses the point entirely. Any athlete whose body has been repeatedly let down will find their relationship with competition changes in exactly this way.

Understanding Why the Body Breaks Down

To understand load management, you first need to understand what load actually is and what happens when the balance tips the wrong way.

At its core, training stress is productive. It causes micro-damage to tissue which, given enough recovery time, comes back stronger. This is how fitness is built. The trouble is that this process has limits, and those limits are different for every person and every tissue type. When the amount of stress placed on the body consistently exceeds its capacity to repair, the damage accumulates. The tissue does not get a chance to fully rebuild before it is loaded again. Over time, this is how acute niggles become chronic conditions.

Elite athletes are, paradoxically, at significant risk here. Their bodies are capable of tolerating enormous amounts of physical stress, which means they are also capable of training at volumes that would destroy the average person. The very qualities that make them exceptional, high pain tolerance, extraordinary drive, the ability to keep going when others stop, can become liabilities if they override the body’s distress signals.

What makes the situation even more complex is that load is not only physical. Psychological stress, poor sleep, inadequate nutrition, and travel fatigue all affect how well the body copes with physical demand. An athlete managing a tough competition schedule whilst dealing with personal pressures off the field is carrying a much heavier cumulative load than their training diary suggests. Ignore that, and the body will find a way to make the point itself.

What Load Management Actually Means

Load management gets a bad reputation partly because it sounds like a euphemism. A way of saying an athlete does not want to play, dressed up in technical language. But that is a pretty uncharitable reading of what it actually involves.

In physiotherapy and sports medicine, load management refers to the deliberate monitoring and adjustment of the total demand placed on an athlete’s body over time. That includes the physical load from training and competition, the psychological load from stress and mental fatigue, and the cumulative load that builds up across a full season or career. A physiotherapist working with a load management programme is not pulling an athlete from a game for no reason. They are making a decision based on data: training volumes, recovery markers, subjective wellbeing scores, tissue response, and sometimes years of individual history.

The distinction that matters most is between avoiding stress and managing it. A well-designed load management programme does not remove physical challenge from an athlete’s life. It structures that challenge so the body can adapt to it rather than be overwhelmed by it. Tissue needs load to stay healthy. Tendons and bones respond to stress by becoming more robust, but only if there is adequate recovery between bouts of loading. The goal is to keep an athlete training at the right level, rather than either overdoing it or going so easy that deconditioning sets in.

This is where physiotherapists earn their keep. Reading the signals an athlete’s body is sending, understanding the difference between productive discomfort and a warning sign, and adjusting plans accordingly is a nuanced, demanding skill. It requires trust between the athlete and the clinician, honest communication, and a willingness from everyone involved to treat the long-term picture as the priority.

The Athlete’s Perspective: Why It Makes Sense

Ask any athlete who has managed a chronic pain condition well what made the difference, and a version of the same answer tends to come back: understanding what was actually happening in my body.

For a long time, the culture of sport made that kind of understanding difficult. Pain was weakness. Sitting out was failing. The athletes who played through injuries were celebrated; the ones who did not were questioned. That culture has not vanished, but it has shifted in meaningful ways, partly because some of the most celebrated athletes in history have been open about what chronic pain cost them and what load management gave them back.

LeBron James is probably the most cited example in professional basketball. The extraordinary attention he gives to his body, the investment in recovery, and the willingness to manage his minutes during the regular season is widely credited with allowing him to perform at an elite level deep into his late thirties, a period when most players have long since faded or retired. Roger Federer managed a career plagued by knee difficulties with meticulous attention to his schedule, pulling out of tournaments that did not suit his body’s needs and returning to peak condition when it mattered. Both careers tell the same story: careful management of the body, rather than avoidance of competition, and a genuine commitment to protecting an asset worth protecting.

The shift in mindset is significant. Rather than asking how much pain can I play through, athletes managed by good physiotherapy teams start asking what does my body need to be available when it matters most. That is a fundamentally different relationship with physical discomfort, and it tends to produce fundamentally better long-term outcomes.

The Science That Backs It Up

Load management is grounded in solid science that continues to grow, not a trend cooked up by risk-averse medical teams.

Pain neuroscience research over the past two decades has dramatically changed how clinicians understand chronic pain. The old model, in which pain reliably indicates tissue damage, has been replaced by a more sophisticated understanding: pain is the brain’s interpretation of a threat, shaped by context, history, expectation, and many factors beyond the state of the tissue itself. This matters for load management because it means addressing chronic pain requires more than resting a sore tendon. It requires helping the nervous system recalibrate its threat response, something that graded exposure, a cornerstone of load management, does particularly well.

Graded exposure involves gradually increasing the load placed on an affected area in a controlled, progressive way. Rather than either avoiding the activity entirely or jumping back in at full intensity, the athlete moves through carefully structured stages that allow tissue to adapt and the nervous system to rebuild confidence. The evidence supporting this approach for conditions like tendinopathy and chronic lower back pain is genuinely compelling.

On the monitoring side, wearable technology has given sports science teams tools that simply did not exist a generation ago. GPS tracking, heart rate variability monitoring, and subjective wellbeing questionnaires allow support staff to build a detailed, ongoing picture of an athlete’s load. Spikes in training volume, a well-established risk factor for overuse injury, can be spotted and addressed before they cause damage. The whole system runs on data-driven decision making applied to the human body, and the research consistently shows that athletes managed within evidence-based load parameters sustain fewer serious injuries over time.

Load Management in Practice Across Different Sports

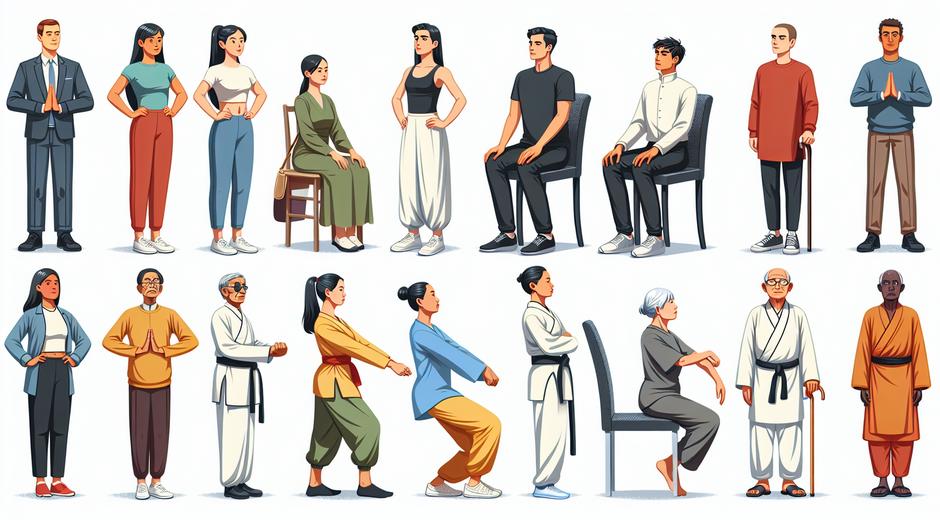

One of the misconceptions about load management is that it looks the same regardless of the sport or the individual. A marathon runner managing chronic Achilles tendinopathy requires a completely different programme from a professional footballer protecting a recurring hip flexor issue, and both differ again from a rower managing persistent lower back pain.

In endurance sports, load management often centres on periodisation, the deliberate structuring of training into phases of high intensity and deliberate recovery. Elite distance runners, for instance, will typically build volume across several months, then taper sharply before a major event. Within that broad structure, a physiotherapist monitoring chronic pain will adjust specific sessions in response to tissue feedback, swapping a long run for cross-training, modifying pace targets, or introducing extra rest days when early warning signs appear.

In team sports, the challenge is different because the competitive calendar rarely allows for ideal preparation. Matches come every few days across a long season, and the temptation to play an athlete who is not fully recovered is always there. Load management in this context involves rotation, careful management of training intensity between games, and a willingness from coaching staff to prioritise availability over a whole season rather than performance in any single fixture.

What both settings share is the involvement of a multidisciplinary team. Physiotherapists, sports scientists, nutritionists, strength and conditioning coaches, and increasingly psychologists all contribute to the picture. No single person has all the information needed to manage chronic pain effectively in a high-performance environment. The best outcomes come when those disciplines talk to each other.

Away from elite sport, load management matters just as much, even if it looks less sophisticated. A club-level footballer running three times a week whilst doing a physical job is accumulating load that deserves attention. A junior athlete growing rapidly is at particular risk of bone stress injuries if their programme does not account for the demands being placed on developing tissue. Access to good physiotherapy at grassroots level remains patchy, but the principles are the same regardless of the level of competition.

Addressing the Criticism

The criticism of load management in professional sport is understandable, even if it often misses the point. When a star player sits out a sold-out fixture citing load management, fans who have paid significant money to watch feel short-changed. Broadcasters who have built entire coverage around that player’s presence have a legitimate commercial grievance. These frustrations are real.

But the frustration tends to collapse the medical rationale into a perception problem. What looks, from the outside, like an athlete choosing comfort over commitment is, more often than not, a medical team making a calculated decision about tissue health and injury risk. The optics are difficult partly because chronic pain is invisible. There is no cast, no crutch, no swollen joint to point to. The athlete looks fine. The decision to rest them looks capricious. It rarely is.

The financial pressures cut in different directions too. On one side, clubs and franchises have a significant financial incentive to protect their most valuable assets. A serious injury to a marquee player costs far more than a missed regular-season appearance. On the other side, short-term commercial pressures, television contracts, and the expectations of paying supporters push in the opposite direction. Load management sits uncomfortably in the middle of that tension, and it is not always handled with the communication and transparency that might help the public understand the reasoning.

The argument for load management, stripped back to essentials, is about availability. An athlete managed carefully across a full season is more likely to be fit for the moments that matter most, the finals, the title run-ins, the tournaments that define careers. The alternative, playing through chronic pain until the body breaks down completely, might produce more minutes in the short term, but it tends to produce much less in the long run.

The Bigger Picture

Load management sits within a broader shift in how sport thinks about athlete welfare, one that has been a long time coming. The old model, in which athletes were expected to sacrifice their bodies for the good of the team, the club, or the competition, is giving way. Slowly, imperfectly, but genuinely, to one in which the person inside the performance is considered worth protecting.

The long-term health implications of unmanaged chronic pain extend well beyond the sporting career. Athletes who play through persistent tendon damage, ignore bone stress injuries, or mask pain with medication rather than addressing its cause can face decades of difficulty after they retire. Joint problems, neurological pain, and diminished mobility in later life are not uncommon among those whose bodies were treated as disposable during their playing days. Load management, done well, is a form of investment in a future that extends beyond the final whistle.

The case for filtering these principles down to youth sport is particularly strong. Young athletes are still developing physically, and the consequences of overloading growing tissue can be severe and long-lasting. The culture around junior sport, in which excessive training volume is sometimes worn as a badge of commitment, deserves more scrutiny than it typically receives. Teaching young athletes to listen to their bodies, to understand the difference between productive discomfort and damage, and to see rest as part of training rather than opposed to it, is one of the most valuable things a physiotherapist or coach can do.

Technology will continue to improve the precision with which load can be monitored. AI-assisted analysis of training data, more sophisticated wearables, and predictive modelling that can flag injury risk before symptoms appear are all developments already underway. The tools are getting better. The challenge remains cultural: making sure the people with the authority to act on the data are willing to do so.

Protecting the Long Game

Athletes load manage because the body has limits, and understanding those limits takes intelligence, not weakness. Chronic pain in sport is not inevitable, but it is common, and it is almost always the result of a system under more stress than it can sustainably handle.

Load management, grounded in pain science, guided by good physiotherapy, and supported by a culture that treats athlete welfare as a priority, is one of the clearest advances modern sport has made. The system is imperfect. The communication around it could be better. The access to it outside elite sport is nowhere near good enough. But the underlying logic, that an athlete who is managed carefully will last longer, perform better, and leave sport in better health than one who is not, is difficult to argue with.

The long game, in sport and in life, belongs to those who respect their body enough to listen to